Less is More: Why We Abandoned Micro-ROS for UART

If you’ve worked on robotics projects, chances are someone has mentioned ROS (Robot Operating System). And if you’re anything like me, you’re always eager to try out shiny new tools.

When we started working on our TWIP (Two Wheel Inverted Pendulum) project, I was determined to use ROS—mainly because it’s a system that countless robotics videos swear by. Augusto saw things differenlty. He argued that “ROS is massive, complex, requires a steep learning curve, and is most definitely overkill for what we’re doing.” His point was valid, but I wanted to explore what ROS could offer. Of course, I didn’t say that. Instead, I just said that communication shouldn’t be our main focus—so why not let ROS handle it?

Since then, our relationship with the ROS ecosystem has been, to put it mildly, turbulent. There is much to cover about the subject. This blog explores a small part of the story, by mainly using micro-ROS.

We aim to show how sometimes software tools—or, as alluded to in this post, abstractions—can be deceptively simple.

Hopefully, our story provides a framework to help you make a more informed decision not just about micro-ros (mentioned below) but any tool.

A Little Bit About the Robot Operating System (ROS)

Contrary to what you may think the Robot “Operating System” (ROS) is not an operating system in the classical sense, but rather a communication layer between different robotic components. Think of it as a sophisticated message-passing system that allows various programs (called nodes) to communicate with each other. Each node can publish messages to specific topics or subscribe to receive messages from topics they’re interested in. This is a very good thing, because components can communicate using different programming languages, physical system and computational capacity.

The TWIP Adventure

Control Problem

TWIP is a control system problem. As any control system, it requires precise timing and immediate response — It’s like trying to balance a broomstick on your palm.

Just as your hand must move quickly and precisely to keep the broomstick upright, our robot’s motors need to respond instantly to keep the robot balanced.

Timing is crucial. The system needs to know exactly when each measurement was taken and when each correction was applied.

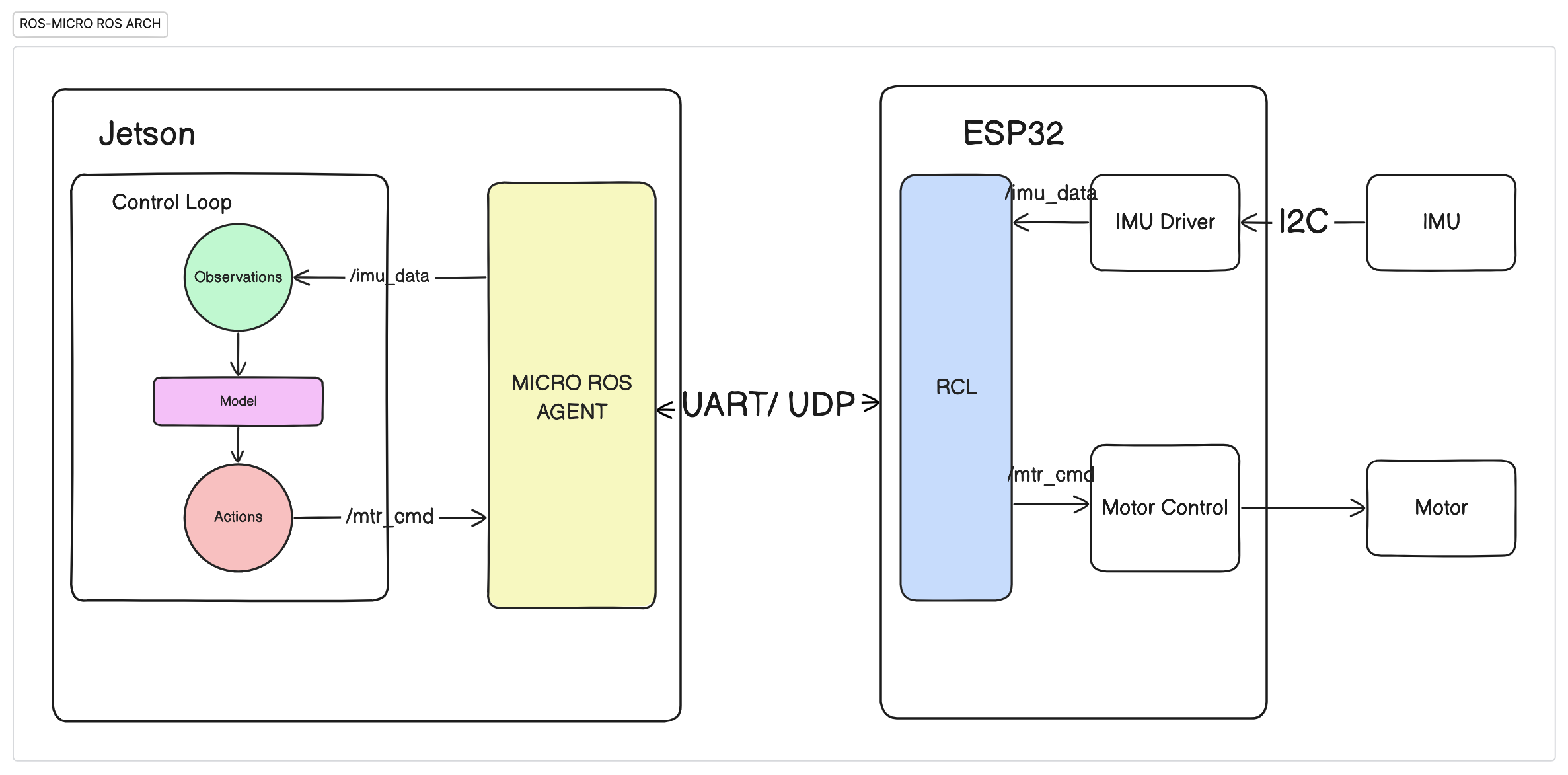

Our initial setup for the TWIP robot comprised a Jetson Nano and an ESP32. The Jetson Nano handles high-level computations, including running an inference model for the control loop. The ESP32 interacts directly with the sensors and motors, providing sensor data and executing motor commands.

The figure below illustrates the setup.

- The IMU timer callback fires at a fixed rate (1kHz in our case) and publishes the pendulum’s angle on the

/imu_datatopic - The control loop runs one iteration, by:

- Reading the current angle

- Calculating required corrective torque

- Publishing motor commands on the

motor_cmdtopic

- The ESP32 subscribes to the

/motor_cmdtopic and triggers the callback when new data is received - The ESP32 outputs a PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) value which translates to output torque

- The physical system responds

- The cycle repeats with fresh IMU data

The Role of micro-ROS and micro-Ros Agent

Microcontrollers like the ESP32 typically lack the computational power and memory to run a full ROS 2 node (remember Augusto’s point about this?).

To address this limitation, we used a micro-ROS Agent.

The micro-ROS Agent running on the Jetson Nano connects to the microcontroller’s micro-ROS client, enabling it to communicate with other nodes in the ROS 2 network as if it were a full-fledged ROS 2 node. The ESP32 runs the micro-ROS client and connects to the micro-ROS Agent via UART, Wi-Fi, or Ethernet. In our case the micro controller can publish and subscribe to the topics /imu_data and /motor_cmd

For more details about micro-ROS agent, you can refer to the micro-ROS Agent GitHub repository.

Here’s a simplified version of the initial code. We initialize Wi-Fi transport, set up the publisher for IMU data, and subscribe to motor commands. The timer and executor ensure continuous data flow, triggering the motor control loop based on incoming sensor readings.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

// Core micro-ROS setup

void setup_uros() {

// Setup wifi transport

set_microros_wifi_transports("SSID", "PASSWORD", "192.XXX.XXX.XXX", 8888);

// Initialize node

allocator = rcl_get_default_allocator();

rclc_support_init(&support, 0, NULL, &allocator);

rclc_node_init_default(&node, "esp_node", "", &support);

// Publisher for IMU data

rclc_publisher_init_default(&imu_pub, &node,

ROSIDL_GET_MSG_TYPE_SUPPORT(sensor_msgs, msg, Imu), "imu_data");

// Subscriber for motor commands

rclc_subscription_init_default(&motor_cmd_sub, &node,

ROSIDL_GET_MSG_TYPE_SUPPORT(sensor_msgs, msg, JointState), "motor_cmd");

// Timer and executor

rclc_timer_init_default(&timer, &support, RCL_MS_TO_NS(1000), timer_cb);

rclc_executor_init(&executor, &support.context, 2, &allocator);

rclc_executor_add_timer(&executor, &timer);

rclc_executor_add_subscription(&executor, &motor_cmd_sub, &motor_cmd_msg, &motor_cmd_cb, ON_NEW_DATA);

}

// Main loop

void loop() {

delay(5);

rclc_executor_spin_some(&executor, RCL_MS_TO_NS(5));

}

// Callbacks

void timer_cb(rcl_timer_t *timer, int64_t last_call_time) {

update_imu_data();

rcl_publish(&imu_pub, &imu_msg, NULL);

}

void motor_cmd_cb(const void *msgin) {

const sensor_msgs__msg__JointState *msg = (const sensor_msgs__msg__JointState *)msgin;

set_motor_values(msg->effort.data[0], msg->effort.data[1]);

}

When Abstractions Started Leaking

There’s a very interesting blog written by Joel Spolsky that highlights a key insight:

All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky.

We experienced this firsthand.

Our challenge began with motor control issues while running TWIP. Sometimes the robot responded perfectly, but more often than not, the motors behaved erratically, with noticeable jittering.

Quality of Service (QoS) and Network Congestion

Micro-ROS introduces Quality of Service (QoS) settings to manage message delivery and buffering. The History Depth option allows storing the last N (specified constant) messages. The

Reliability setting offers two options: RELIABLE, which guarantees message delivery with retries but may cause delays, and BEST_EFFORT, where messages are dropped if delivery fails.

Additionally, NBC (Network Congestion Batching) helps reduce overhead by batching messages during network congestion, improving communication efficiency.

The Impact on Control

We encountered a classic control systems problem where seemingly reasonable design choices—such as using RELIABLE QoS for safety and handling delayed commands—combined to create an unstable system.

The combination of the RELIABLE QoS setting, network congestion, and a small but deadly 5ms delay resulted in erratic motor behavior. For every 1 IMU callback, 10 motor commands were fired, overwhelming the control loop. This delay alone, probably cost us two weeks of development time.

- The IMU timer callback fires at a fixed rate (1kHz) and publishes the pendulum’s angle

- An initial motor command triggers with a 5ms set_torque() delay

- During this blocking delay, the executor itself is blocked

- No new callbacks can be processed

- IMU readings can’t be handled

- New motor commands can’t be processed

- Meanwhile, due to RELIABLE QoS

- Messages are accumulating in the transport layer

- Nothing is dropped, everything is queued

- When the blocking delay ends:

- The executor suddenly processed its backlog

- Queued commands execute in rapid succession

- Each command based on increasingly stale data, thus responding to outdated pendulum positions

- The system over-corrects, making the instability worse and generating more commands needing correction

- Next blocking delay occurs, repeating the cycle and accelerating the positive feedback loop

Leaky Abstraction

A leaky abstraction occurs when high-level interface (micro-ROS in our case) fails to completely hide low-level implementation details, forcing you to understand the underlying complexity that it was trying to hide. My initial reasoning was that we should avoid communication and use an abstraction. However, the “simple” abstraction provided by micro-ROS forced us to confront complex topics, including:

- Network transport layers

- Message buffering mechanisms

In hindsight, there is a couple of solutions we could have implemented, but not knowing the system well, we simply overlooked. We ended up using a simpler solution: UART communication.

A Simpler Solution

this an example of sending motor commands

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void tx_task() {

char send_buf[16];

while (true) {

send_buf[0] = 's'; // start marker

send_buf[1] = 'f'; // data type

memcpy(send_buf + 3, &imu_data.roll, sizeof(float));

uart_write_bytes(UART_NUM_1, send_buf, sizeof(send_buf));

vTaskDelay(50 / portTICK_PERIOD_MS);

}

}

THAT’S IT! Other than the serialization and deserialization, the system was:

- Predictable

- Easy to debug

- Free from hidden complexities

- Direct and transparent

The Paradox of Abstration

In Spolsky’s blog, he points out:

“Abstractions save us time working, but they don’t save us time learning.”

When abstractions work, they’re magical! But when they fail, you need to understand:

- The abstraction itself

- The underlying system it’s hiding

- How they interact

How to Make the Choice

So, should you use micro-ROS in your project?

As with any engineering decisions, there’s unfortunately no one-size-fits-all answer.

However, here’s a framework that may guide your decision making for any tool, not just for micro-ROS:

Before adopting any new technology, ask yourself 2 questions:

- What’s the learning budget?

- What’s the complexity-benefit ratio?

Some frameworks are worth the investment because they solve a bigger, harder, overall problem. For example, we stuck with ROS for our Newton project because the perception and planning aspect introduces a camera, IMU, and sensor fusion making it simpler to deal with ROS. We have encountered a lot of annoyances with ROS but the overall problem that it solves is worth the trouble.

That being said, for other projects, like TWIP, the learning investment might have outweighed the benefits. You may not know what the complexity-benefit ratio is, but keep it in mind as you go through exploring the technology.

The Takeaway

Whether you choose micro-ROS or any other tools, be prepared for the leaks. In the world of software, they’re not a matter of if, but when. Sometimes, as we learned, the simplest solution might be the most robust one. Or it might be too robust, but requires heavy investment in learning it.